For our last blog post of 2023, we wanted to bring you something diverting to read on the longest night of the year. We don’t pretend to be experts on the etymology of the word ‘solstice’, but we enjoyed finding out what we’ve included here; if anyone knows more about it, we would love to hear from you!

The etymology of solstice: from Latin to Middle English

The English word ‘solstice’ derives from the Latin solstitium, and refers to the two dates in each year when the daylight hours are at their longest or shortest.

Nam melior est autumnalis [agnus] verno, sicut ait verissime Celsus; quia magis ad rem pertinet, ut ante aestivum quam hibernum solstitium convalescat solusque ex omnibus bruma commode nascitur.

Columella, On Agriculture 7.3.11-12

(died c. 70 CE)

For an autumn lamb is superior to a spring lamb, as Celsus very truly remarks, because it is more important that it should grow strong before the summer solstice than before the winter solstice, and it alone of all animals can be born without risk in mid-winter.

(Harrison Boyd Ash, 1941)

However, solstitium in Latin more commonly referred to the summer solstice, whilst the winter solstice was usually indicated by the word bruma.

Dicta bruma, quod brevissimus tunc dies est; solstitium, quod sol eo die sistere videbatur, quo ad nos versum proximus est. Sol cum venit in medium spatium inter brumam et solstitium, quod dies aequus fit ac nox, aequinoctium dictum.

Varro, On the Latin Language, 6.8

(116–27 BCE)

Bruma was so named, because that is when the day is ‘shortest’ (brevissimus): the solstitium, because on that day, when it is nearest to us, the ‘sun’ (sol) seemed ‘to halt’ (sistere). When the sun has arrived midway between the bruma and the solstitium, it was called the aequinoctium, because the day becomes equal to the night.

(Roland G. Kent, Ph.D., 1938, slightly adapted)

Based on the surviving texts, it seems that it took a few centuries for ‘solstice’ to assert full authority over ‘midwinter’s day’ — both in Latin and in what would become English.

Whilst not all late antique texts have been digitised, a fair number of those that are readily available appear to quote or define for the reader some much earlier usages of bruma from the classical era, as if it was by thenno longer a commonly used word.

BRVMA id est hiemps. Dicta autem ‘bruma’ quasi βραχὺ ἦμαρ, id est brevis dies. Est autem, ut hic locus indicat, generis feminini, numeri singularis.

Servius, Commentary on Vergil’s Aeneid, 2.472

(floruit late 4th C-early 5th C CE)

BRUMA: that is, ‘winter.’ But bruma was said to possibly be from βραχὺ ἦμαρ, which is ‘short day.’ Moreover, as this line shows, bruma is feminine singular.

From classical usage to Christian censorship

Could it be that bruma was being replaced by some other midwinter holiday?

It probably didn’t help that the Pope outlawed the raucous brumalia (the winter solstice festival) in 743 CE.

Ut nullus Kalendas Januarias et broma (= brumalia) colere praesumpserit, aut mensas cum dapibus in domibus praeparare, aut per vicos et plateas cantationes et choros ducere, quod maxima iniquitas est coram Deo: anathema sit.

(Acta Conciliorum, Parisiis, 1714, Vol. III., col. 1929, Concilium Romanum, I., A.D. 743, ix)

Let no one dare to celebrate the first day of January and the brumalia, or to prepare tables with feasts at home, or to lead songs and dances through the towns and streets, which is the greatest offence before God: let it be anathema.

The etymology of solstice beyond Latin: from sunnstede to brume

Meanwhile over in England, the Anglo-Saxons were already referring to both solstices with the word sunnstede.

Gǽþ seó sunne norðweard óð ðæt heó becymþ tó ðam tácne ðe is geháten Cancer, ðǽr is se sumerlíca sunnstede; for þan ðe heo cyrð ðǽr ongeán eft suðweard; and se dæg þonne sceortað óð ðæt seó sunne cymþ eft súð tó ðam winterlícan sunnstede, and ðǽr ætstent.

Bede, De Temporibus 4

(672-735 CE)

The sun goes northward until it comes to the sign that is called Cancer; there is the summer solstice, because there it turns back southward, and then the day shortens until the sun comes again south to the winter solstice, and there stands still.

(Rev. Oswald Cockayne, 1866, adapted)

Back on the continent, the forms and meanings of bruma and solstitium were rapidly changing — rapidly, that is, if you go by the watch of a philologist.

In the 1260s, bruma appears in old French as brume in Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Tresor, a very early encyclopedia. Although brume means ‘mist’ in modern French, at this time it stills seems to have meant ‘winter’.

Et en cele terre habitent homes molt petis, mais il sont si hardis qui’il osent bien contrester au cocodril … Et quant il est dedens le fleuve, il ne voit gaires bien; més en terre voit il mervilleusement. Et tot yvier ne manguë, ains endure et suefre sain tous les iiii mois de brume.

Brunetto Latini, Li livres dou Tresor, I.V.CXXXII

1260-1267 CE

And in this land live many small people, but they are so bold that they dare to go up against the crocodile … And when it is inside the river, it cannot see well; but on land it sees wonderfully. And the whole winter it does not eat, but endures and stays healthy all four months of winter.

You may recognise Mr Latini’s name from various contexts — he was also Dante Alighieri’s teacher. Dante wrote him into the Inferno, where he can be found suffering in the seventh circle of hell for the sin of sodomy.

The next surviving attestation of brume seems to be in Poème sur la grande peste de 1348, (1426 CE) where it means a heavy mist, probably reflecting the medieval belief that miasma carried disease. .

Et doit on tousdiz refuser

Toutes eaues & non user

Des rivières & des fontaines

Qui décourent parmi les vaines

De souffre, métaulx & allume,

Et couvertes de forte brume.

Anonymous, Poème sur la grande peste de 1348, lines 2018-2023

1426 CE

And we must always refuse

All water and not use

Rivers & fountains

That run among the veins

Of sulphur, metals & alum,

And are covered with heavy mist.

As for what remained of Latin solstitium, The Norman Conquest managed to import into England the newfangled old French word solstice.

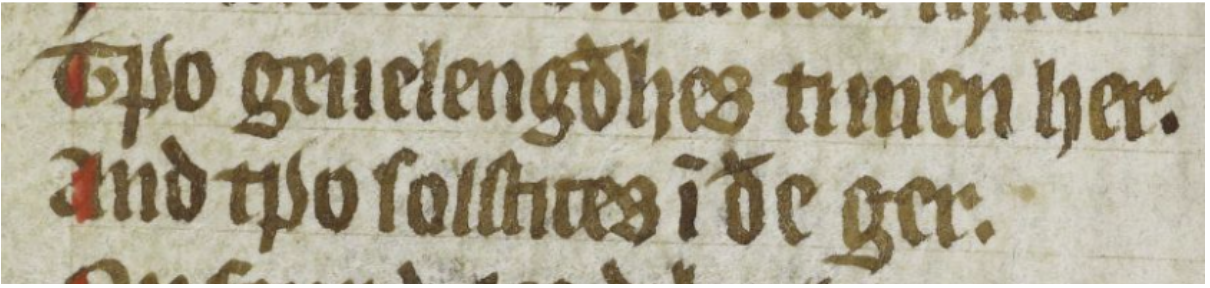

One of the earliest attestations in English of ‘solstice’ — if not the earliest — is a Middle English verse paraphrase of the Historia scholastica (itself a Biblical paraphrase in medieval Latin by Petrus Comestor).

And egest swich ðe sunnes brigt,

Is more ðanne ðe mones ligt.

ðe mones ligt is moneð met,

ðor-after is ðe sunne set;

In geuelengðhe worn it mad,

In Reke-fille, on sunder shad;

Two geuelengðhes timen her

And two solstices, in ðe ger.

The Middle English Story of Exodus and Genesis, lines 143-150

circa 1250 CE

And highest such is the sun’s brightness

It is more than the moon’s light.

The moon’s light is month-measure,

Thereafter is the sunset.

In the equinox was it made,

In mist-filled [April], on sundry shade;

Two equinoxes happen here

and two solstices, in the year.

(Cockayne, 1866, adapted)